The A-B-C formula for strength and athleticism

While there’s no set-in-stone “best” way to structure a single workout, I’m going to give you my super-secret formula for getting stronger and more athletic by following a system that’s as easy as A-B-C.

(Note: I borrowed this system from legendary coach, Tony Gentilcore. He’s can deadlift a brick house, so he knows what he’s talking about.)

I have adapted this formula to build workouts for the skiers, snowboarders, climbers, and hikers I work with. If you’re reading this, I’m going to assume you share a couple things with the people I work with. First, that you want to be strong and agile to handle the demands of your sport; and secondly, that you want results in as little gym time possible (because life is generally more fun lived outside).

If that sounds like you, read on.

Here’s the simple A-B-C formula I use to write effective workouts:

Athlete: Dynamic warm up + plyometric exercises to prime your muscles

Build: Strength work in various rep ranges

Conditioning: Basically “cardio,” but the goal is to improve different energy pathways (aka, how our bodies turn carbs/fats into fuel for activity)

Athlete phase

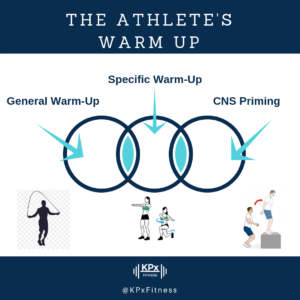

Starting with a dynamic warm up prepares your body for the workout you’re about to do and helps reduce injury risk. Plyometric exercises prime your muscles to fire efficiently.

(Read more about effective warm ups here.)

(Read more about effective warm ups here.)

Plyometrics include any explosive jumping or throwing motion: squat jumps, broad jumps, jump lunges, skaters, high skips, box jumps, medicine ball throws and slams, plyo or clapping push ups, and so on.

The intention of plyometric exercises is to produce as much force as possible. Given that goal, you should keep reps low for plyo exercises and rest until you’re completely recovered between sets. Three to five sets of 3-6 reps with 90-120 seconds of rest is a good rule of thumb.

These explosive movements fire up your central nervous system so that your nerves send faster signals to your muscles, which will make the next phase of your workout more effective.

Build phase

The “main course” of your workout, so to speak. This is where you use resistance training to build strength and stimulate muscle growth (before anyone freaks out, muscle growth is how you get that toned/defined look).

You can build strength with moderate-to-heavy weights in a variety of rep ranges, and you should vary the reps you use during your workouts.  How many reps, exactly? Train 1-3 reps for power; 4-8 reps for strength; 8-12 reps for strength-hypertrophy; 10-15+ reps for strength-endurance. Most people should live in the 6 to 12 or 15 range, unless you have a specific interest in training with maximal loads.

How many reps, exactly? Train 1-3 reps for power; 4-8 reps for strength; 8-12 reps for strength-hypertrophy; 10-15+ reps for strength-endurance. Most people should live in the 6 to 12 or 15 range, unless you have a specific interest in training with maximal loads.

I generally structure my own workouts and my clients’ workouts like a pyramid, with heavier, lower-rep exercises at the beginning when you’re most fresh (and coming off the plyometric/priming exercises). Each subsequent set of exercises works a slightly higher rep range.

For example, a workout might start with 3×5 box jumps to prepare your legs for squats. Then 4×5-6 heavy squats for strength. Then we’d throw in some “accessory” exercises that train the same muscles used in squatting (glutes, quads, hamstrings). This could look like a superset of dumbbell deadlifts and split squats for 3-4 sets of 10-12 reps.

Regardless of the rep range you’re working in, the key is using the right weight. You should select weights that feel like a 7-8 out of 10 effort for each set. You don’t want to train to failure, but you want to feel like you’re approaching that point at the end of every set.

Conditioning phase

This is what many people consider the “fun” part of the workout because it’s where your heart rate increases and you get all sweaty and out of breath.

The key to conditioning is to challenge your body’s different energy systems. Long story short, your body has different systems that produce different amounts of energy for different levels of time and intensity.

There are three energy systems: the immediate (ATP-CP) energy system, the glycolytic system, and the oxidative system. All three systems work simultaneously to a degree, but one system will dominate energy production depending on whatever activity you’re doing.

- The immediate energy system supplies explosive, rapid response energy. For example, a tall box jump or a one-rep max of a fast and heavy lift. This system powers activities that last only 3-10 seconds and requires about 90 seconds to recover between efforts.

- The glycolytic system copes with demands that require a relatively high energy output for a relatively short amount of time–such as a sprint down the ice in a hockey game. This system provides power lasting up to 60 seconds.

- The oxidative system copes with lower output work for longer durations of time, such as a jog or hike.

In practice, you might train the immediate energy system once or twice a week with sprints up to 10 seconds, followed by lots of rest (60-90 seconds).

And you might train the glycolytic system once or twice a week with 30-60 seconds of work, followed by 1-2x as much recovery time.

Finally, you can train the aerobic system fairly often at low intensity (daily walking) or a couple times each week at moderate intensities (running/jogging).

There’s no single “best” way to approach conditioning. The best approach for you really depends on your current fitness level and personal goals. Bottom line, try to train each of the three systems throughout the week for the most cardio benefit.

Making the A-B-C’s work for you

Just as there’s no set-in-stone “best” way to structure a workout, there’s no best way to set up your own training calendar.

The cool thing is, you can apply the A-B-C formula to your workouts whether you train once a week, twice a week, or 5-6 times each week.

If you’re doing fewer workouts (1-3) they should be full body. Pick an exercise from each movement pattern.

- Squat/lunge: Squat, split squat, lunges, step up, etc

- Hinge: Deadlift, Romanian deadlift, bridge, hip thrust, pull through, etc

- Push: Bench press, floor press, shoulder press, push ups, dips, etc.

- Pull: Pull ups, chin ups, pulldowns, bent over row, single-arm row, cable row, pull over, etc.

If you’re doing 4-6 workouts per week, you can stand to divide up your training sessions and focus each workout on something specific. Good examples include upper/lower body, push/pull, push/pull/legs, or other training splits. (More on effective training splits.)